Iain Miles gave a fascinating and detailed talk in February about the Land Drainage of the Somerset Levels and the importance of Westonzoyland Pumping Station.

He introduced the subject  by setting it in a landscape context. He explained how the basin at the heart of the Somerset Levels is surrounded on three sides by high ground in the form of Exmoor, the Brendons, the Blackdowns, the Poldens and the Mendip ridge. The rivers originating in these hills flow into the basin and most join the Parrett to flow into the sea to the north of Bridgwater. The silt from these rivers has been deposited in the basin over millennia and the area as we see it today is a flat or level surface rarely more than 10ft above OD and with only a very small gradient on its rivers once they leave the hills. The character of the area and its tendency to flood is therefore partly due to the effect of heavy rainfall on the hills and the inability of the rivers to transport water quickly to the sea, but also to the high tidal range in the Bristol Channel. At times of high spring tides, the sea can penetrate inland and overwhelm a river system struggling to transport its load to the sea. Clyses or tidal doors have been constructed to prevent the sea from penetrating inland and the earliest of these to be documented is the Highbridge Clyse recorded as being already in existence by 1485.

by setting it in a landscape context. He explained how the basin at the heart of the Somerset Levels is surrounded on three sides by high ground in the form of Exmoor, the Brendons, the Blackdowns, the Poldens and the Mendip ridge. The rivers originating in these hills flow into the basin and most join the Parrett to flow into the sea to the north of Bridgwater. The silt from these rivers has been deposited in the basin over millennia and the area as we see it today is a flat or level surface rarely more than 10ft above OD and with only a very small gradient on its rivers once they leave the hills. The character of the area and its tendency to flood is therefore partly due to the effect of heavy rainfall on the hills and the inability of the rivers to transport water quickly to the sea, but also to the high tidal range in the Bristol Channel. At times of high spring tides, the sea can penetrate inland and overwhelm a river system struggling to transport its load to the sea. Clyses or tidal doors have been constructed to prevent the sea from penetrating inland and the earliest of these to be documented is the Highbridge Clyse recorded as being already in existence by 1485.

For many years the area was largely uninhabited. Only small islands punctuated what was a largely wetland area and these attracted monks seeking solitude. Monasteries developed from this and initially there was no problem with self- sufficiency. There was fertile land above the flood level and the rivers provided abundant fish and wildfowl. The marshlands also yielded peat for fuel. By the thirteenth century, however, the monastic estates already owned most of the land and their needs had grown to the point where it became necessary to increase production by draining areas. The earliest reclamation took place around the higher land where the alluvial soil was more fertile. Rivers were straightened, primarily for navigation, and raised walls or embankments built to prevent flood water incursions. It is likely that the river Parrett was fixed in its course at this time. The thirteenth century, Iain felt, saw the establishment of much of the modern river system.

Economic conditions in the fourteenth century however deteriorated and little documentation exists for any further monastic activity prior to the Dissolution. In fact, the landscape must have remained largely unchanged until the enclosures of the second half of the eighteenth century and the first half of the nineteenth. The enclosures brought an increased interest in land improvement and surveyors and engineers became involved. From 1818 experiments with steam pumping had taken place on the Fens and in 1831 local landowners obtained an Act of Parliament entitled “An Act for Draining, Flooding and Improving certain low lands and Grounds within the several Parishes of Othery, Middlezoy and Westonzoyland in the County of Somerset”. By February 1834 the Taunton Courier is reporting that:-

“…The Steam Engine erected at Westonzoyland has kept the side of the moor from being flooded. The farmers derived great benefit thereby.”

Westonzoyland was therefore the first steam powered pumping station in Somerset and its success was followed by the erection of a second steam engine, this time at Southlake. Further schemes followed and these are all fully documented and illustrated in Iain Miles’s excellent booklet listed below. It was not, however, until the Land Drainage Act of 1930 that a body was created that assumed responsibility for all the main rivers in the County. This was called The Somerset Rivers Catchment Board. Louis Kelting, (pictured below) later the Board’s Chief Engineer, wrote on this period

“There was much preparation of grandiose schemes whose main virtue seemed to be that they invoked strenuous opposition from other authorities”.

None-the-less, he achieved a great deal and in 1941 the first steam plant was replaced with a pair of diesel engine pumps. This was followed, once peace retuned after the war, with more stations being converted from steam to diesel and Westonzoyland was converted in 1950. The Westonzoyland diesel pump is now only used when conditions are bad, normally for 2-3 weeks a year. But, like other diesel pumps in the area it is kept in working order in case of need.

The Westonzoyland Pumping Station today is also a museum and houses the largest collection of stationary steam engines and pumps in the south of England. The fact that so much is preserved is thanks to Louis Kelting who attempted to preserve the redundant steam pumps in their original buildings and, where not possible, stored them at the Old Allermoor Pumping Station.

In his booklet, Iain Miles comments that

“Even people living on or near the levels frequently do not appreciate the organisation, sheer blood, sweat and tears that have gone and are still going into keeping Somerset dry, and safe to live and work in.”

Perhaps those of us who listened to his talk have just a little more appreciation of this than we had at the start of the evening. Madeleine Roberts

Further Reading:

“…Bogs and inundations….” by Iain Miles

“The Draining of the Somerset Levels” by Michael Williams

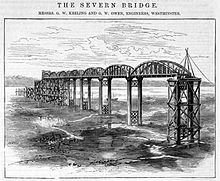

The bridge was constructed between 1875 and 1879 by the Severn Bridge Railway Company primarily to carry coal from the Forest of Dean to the docks at Sharpness, the Lydney docks being too small to cope with the growing volume of trade. It continued in use for freight and some passenger services until 1960, the time of the disaster. It was designed by George Baker Keeling and constructed by Hamilston’s Windsor Ironworks Company Ltd of Garston, Liverpool. The bridge carried a single track railway and trains had to complete the return crossing from Sharpness to Lydney in reverse. It had been hoped that the line would attract tourist traffic as well as local passengers but seven years later the Severn tunnel was opened and, from early on, this threatened the bridge’s financial viability.

The bridge was constructed between 1875 and 1879 by the Severn Bridge Railway Company primarily to carry coal from the Forest of Dean to the docks at Sharpness, the Lydney docks being too small to cope with the growing volume of trade. It continued in use for freight and some passenger services until 1960, the time of the disaster. It was designed by George Baker Keeling and constructed by Hamilston’s Windsor Ironworks Company Ltd of Garston, Liverpool. The bridge carried a single track railway and trains had to complete the return crossing from Sharpness to Lydney in reverse. It had been hoped that the line would attract tourist traffic as well as local passengers but seven years later the Severn tunnel was opened and, from early on, this threatened the bridge’s financial viability.

The decision to demolish was taken and demolition was completed between 1967 and 1970. Today all that remains to be seen are several piers on the embankment and, at low water, the wreckage of the two barges which remain on the river bed.

The decision to demolish was taken and demolition was completed between 1967 and 1970. Today all that remains to be seen are several piers on the embankment and, at low water, the wreckage of the two barges which remain on the river bed.

urday May 20th with a visit to Christon Church. Christon is a small village on the southern slope of Mendip and at the foot of Flagstaff Hill. It looks across the Lox-Yeo valley to Crook Peak and as people gathered many commented on the stunning setting and how tranquil and peaceful the valley must have been before the coming of the motorway.

urday May 20th with a visit to Christon Church. Christon is a small village on the southern slope of Mendip and at the foot of Flagstaff Hill. It looks across the Lox-Yeo valley to Crook Peak and as people gathered many commented on the stunning setting and how tranquil and peaceful the valley must have been before the coming of the motorway. The chancel has been divided into two by a reredos to create a small vestry under the east

The chancel has been divided into two by a reredos to create a small vestry under the east