Joe and Christine King

Another difficult talk to describe without the illustrations. Although all the maps had a function they were also very decorative and it is that which makes them very interesting to look at. I will put some example on the website.

Joe started by saying how intriguing it was that Somerset was so well mapped and explained that this was because in the Elizabethan era they were very fearful of Catholic opposition to Elizabeth 1 and it was felt that her position was insecure. Her Chancellor, Lord Burghley was very anxious about the security of the throne and saw the value of having maps for defence and administration purposes.

He asked Thomas Seckford to arrange for the mapping of the country and he, in turn, asked Christopher Saxton to do this. Saxton had been a servant of John Rudd, vicar of Dewsbury who had, himself, tried to map the kingdom but couldn’t complete the task because it needed the assistance of all the great landowners.

He had been helped by Saxton and it was Saxton who the Privy Council asked to undertake the mapping of the kingdom and all the great landowner were instructed to give him assistance. He used a crude form of triangulation using the beacons, which were on all the high places and in five years had mapped the whole country. Somerset was one of the first places to be mapped and Joe showed the first published map of Somerset produced by Saxton, which is a fairly good representation of the county.

There are lots of decorative details on it, fish, boats, the coat of arms of Elizabeth 1 and also of Seckford which states “Sloth is the country’s bane”. The scale was of the military mile ie 1000 paces. The mile that we recognise today was fixed in 1592 but, as Joe pointed out, for the next 180 years or so many maps had a short mile, a middle mile and a long mile on them. No-one knows why.

The people who made the maps were Flemish craftsmen who had come to England. The early maps were made on copper sheets, which were hammered flat and then the map was scribed on them. Names of course had to be done in mirror writing – very clever as Joe said. After about 300 copies of a map the sheet had to be scribed again.

The early maps showed various places such as Cheddar, Axbridge and Wookey Hole but it is the rivers that predominate. These and the bridges over them were, of course, the most important features to show given their significance for trade and travel. Roads were not shown until later and hills on the early maps looked like little mole hills. The depiction of hills was refined later.

Another main feature of these early maps was the inclusion of deer parks. Mappers had, of course, to be polite to important people but a deer park was also the site of an annual general muster for the villagers to prepare for war.

Given that Saxton had started with no idea of the shapes of counties, his maps were an extraordinary achievement. Editions of the maps, which were in black and white were produced for the next 100 years, although some were hand-coloured.

The next maps Joe showed were those of John Speed produced around 1610.

Speed was an historian who, when James 1st came to the throne was tasked with proving a direct lineage from James to the Greek heroes. No mean feat!

Joe showed Speed’s map of 1612. This shows, in one corner, a town plan of Bath complete with the heraldry of important people on it. It was the first map of the city and shows various details; baths, a horse bath, trees etc. It was very informative as a map and also shows the first reference to a tennis court. Perhaps the major change from previous maps was that it shows the Hundreds for the first time, which were, of course important administratively. One question Joe raised was whether old maps were always correct. There were, of course, errors, but for many years the early maps were replicated by others and so the errors remained. As an example he showed Speed’s Wiltshire map, which shows two villages, now known as North and South Burcombe. On the original drawing Speed had written Quare (meaning query) next to North Burcombe and this was then engraved. For the next 162 years or so the “village of Quare” remained on the maps until the mistake was spotted.

Joe showed Speed’s map of 1612. This shows, in one corner, a town plan of Bath complete with the heraldry of important people on it. It was the first map of the city and shows various details; baths, a horse bath, trees etc. It was very informative as a map and also shows the first reference to a tennis court. Perhaps the major change from previous maps was that it shows the Hundreds for the first time, which were, of course important administratively. One question Joe raised was whether old maps were always correct. There were, of course, errors, but for many years the early maps were replicated by others and so the errors remained. As an example he showed Speed’s Wiltshire map, which shows two villages, now known as North and South Burcombe. On the original drawing Speed had written Quare (meaning query) next to North Burcombe and this was then engraved. For the next 162 years or so the “village of Quare” remained on the maps until the mistake was spotted.

Joe then showed a strange and unusual 1612 map by Michael Drayton who was a contemporary of Shakespeare. This showed women with trees growing out of their hair, ladies with cities on their heads and all manner of weird images.

Must try and find it for the website!

The Saxton and Speed were large and bound as books. In 1626 a map was produced by John Bill, which was of a size that could be put in a saddle bag and reflects the fact that people were moving about more and maps were useful to have with you. Knowing distances was also useful and the next map Joe showed was from 1625 and produced by John Norden who invented a table, which showed the distances between various places.

From then on, there were various innovations which I will just outline briefly.

John Ogilvy produced strip maps which covered the routes that people would commonly travel and which showed various landmarks you might see on your journey.

In 1676 maps were produced by Robert Morden which, for the first time showed roads. The first maps he produced were actually on the back of playing cards and these are now very rare collectors items. In 1695 Morden produced larger maps but interestingly these had no roads marked on them but did have 3 different mile scales despite the fact that it was over 100 years since the government had set the statutory mile we know today. These continued to be published after his death and the smaller plates were also produced with the roads marked.

Further changes to maps reflected wider social changes for example the addition of things of interest, which gave people more information about the places they were visiting. One example shown was of a map by Herman Moll, a friend of Daniel Defoe which included depictions of various antiquities . Similarly John Gibson produced a small map with commodities such as corn, lead, woad, Bristol stone and lapis calaminaris (calamine) illustrated on it.

Strachey produced a vertical map of mining at Chew Magna showing what was going on underground. Although he was the first to do this he has received no credit for doing so and it was a William Smith who later produced similar maps and took the credit. Joe also showed a lovely county map done by Strachey with a plan of Wells on it complete with cathedral and houses.

New maps following the draining of the moors around 1769 showed that roads were then the dominant feature not rivers. Maps around this time were the last to be produced on copper and soon engravings on steel replaced them. These enabled the map-makers to have much finer lines and more detail.

In the 19th century maps began to have a wider use, often reflecting economic changes. George III commissioned maps, which showed the agricultural use of the land for example. By 1820 mail coach roads were shown on the maps and around 1840 there were maps showing canals and later, ones showing railway lines also appeared. Such was the proliferation of railway building that maps were sometimes produced by the railway companies to advertise new lines that were never actually built!

County maps were, of course, still being produced and from 1812 some were in colour and Joe showed several examples. Many of them showed a lot of detailed information reflecting the Victorian desire for self-improvement.

Not all maps were decorative, however. Joe showed an example of what he called a “very miserable map” which was produced by William Cobbett.

The last decorative map was produced by Thomas Maule in 1838.

In conclusion Joe showed some strip maps, and some maps of Somerset where the county looked nothing like Somerset. One produced in 1742 made Somerset look like Africa. Finally, Joe urged everyone to keep a look out for old maps which do turn up occasionally in unlikely places. Some playing card maps recently made £1500 at auction!

An interesting talk and there was plenty to look at. Joe and Christine had a fine display of their maps around the room.

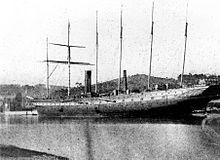

it; this was the Great Western Steamship Company and the directors decided to appoint Isambard Kingdom Brunel as their chief consulting engineer. Although Brunel had never designed a ship before, he was asked to do so on the basis of his work with the Great Western railway.

it; this was the Great Western Steamship Company and the directors decided to appoint Isambard Kingdom Brunel as their chief consulting engineer. Although Brunel had never designed a ship before, he was asked to do so on the basis of his work with the Great Western railway.

Although the contract for the Royal Mail to the US was subsequently given to Cunard the company realised that iron ships were the way forward.

Although the contract for the Royal Mail to the US was subsequently given to Cunard the company realised that iron ships were the way forward.

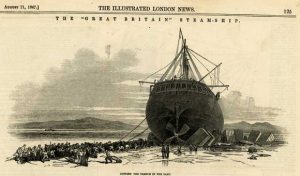

Brunel travelled over there to oversee the ship’s recovery. Fearing the approach of winter storms he made a breakwater around the stern of the ship which saved it from the worst of the winter weather but, although it was successfully re-floated and returned to Liverpool the following year, the cost involved had been enormous and the Great Western Steamship Company went bankrupt, forcing the sale of the SS Great Western and the SS Great Britain to Gibbs Wright and Co in 1847

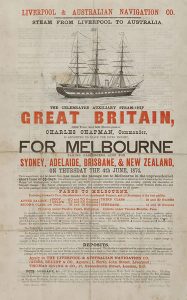

Brunel travelled over there to oversee the ship’s recovery. Fearing the approach of winter storms he made a breakwater around the stern of the ship which saved it from the worst of the winter weather but, although it was successfully re-floated and returned to Liverpool the following year, the cost involved had been enormous and the Great Western Steamship Company went bankrupt, forcing the sale of the SS Great Western and the SS Great Britain to Gibbs Wright and Co in 1847 When gold was discovered in Australia in 1851, there was a sudden massive demand for ships to take people out there and the ship underwent a radical re-fit by the new owners Gibbs Bright & Co to become a 3 masted square–rigged sailing ship with auxiliary engines, which could do the voyage non-stop from Liverpool to Melbourne. In 1852 they carried 700 passengers. It cost 70 guineas (equivalent now to £5000) to travel to Melbourne first class and even in steerage it cost the equivalent of £1500 in today’s money. The journey took just 2 months.

When gold was discovered in Australia in 1851, there was a sudden massive demand for ships to take people out there and the ship underwent a radical re-fit by the new owners Gibbs Bright & Co to become a 3 masted square–rigged sailing ship with auxiliary engines, which could do the voyage non-stop from Liverpool to Melbourne. In 1852 they carried 700 passengers. It cost 70 guineas (equivalent now to £5000) to travel to Melbourne first class and even in steerage it cost the equivalent of £1500 in today’s money. The journey took just 2 months. invaluable resource in piecing together what life was like on board.

invaluable resource in piecing together what life was like on board.

The cost of repairing the ship was considered uneconomical and so she was sold to the Falkland Island Company for £2000 where it became a warehouse primarily for coal, wool and grain and was moored at Port Stanley Harbour. It remained there until it was so rotten that they moved it to Sparrow Cove in 1937 where it was scuttled. Despite being abandoned, she still had some uses. In WWI she was used as a bunkering station and in WWII plates were taken off her to repair damage which had occurred to the HMS Exeter during the Battle of the River Plate. Throughout her time at Sparrow Cove the children of the island greatly enjoyed her presence, using her as an adventure playground and picking mussels from the hull to take home for their tea.

The cost of repairing the ship was considered uneconomical and so she was sold to the Falkland Island Company for £2000 where it became a warehouse primarily for coal, wool and grain and was moored at Port Stanley Harbour. It remained there until it was so rotten that they moved it to Sparrow Cove in 1937 where it was scuttled. Despite being abandoned, she still had some uses. In WWI she was used as a bunkering station and in WWII plates were taken off her to repair damage which had occurred to the HMS Exeter during the Battle of the River Plate. Throughout her time at Sparrow Cove the children of the island greatly enjoyed her presence, using her as an adventure playground and picking mussels from the hull to take home for their tea.

ven a guided tour of the cave where bones can still be seen. These Pleistocene animal bones were discovered in the early part of the 19th century on land owned by George Henry Law, the Bishop of Bath and Wells and, although many of them were removed, some are still carefully stacked around the walls of the chamber.

ven a guided tour of the cave where bones can still be seen. These Pleistocene animal bones were discovered in the early part of the 19th century on land owned by George Henry Law, the Bishop of Bath and Wells and, although many of them were removed, some are still carefully stacked around the walls of the chamber.