A talk by John Page

John started by showing a map of the lighthouses of Somerset including one at Hinkley Point, three at Burnham, two at Clevedon and one which is not in Somerset but which is very important for ships entering the Bristol Channel which is on Flat Holm. Although lighthouses are, of course, there as a warning to shipping and to aid navigation it is, as Daniel Defoe pointed out, the land with its rocks and sand banks and not the sea that makes a storm lethal to ships. John explained that on old maps the Bristol Channel was actually called the Severn Sea. He then showed a video of a map which shows where the various lighthouses are in Somerset, a map complete with appropriate flashing lights. There are a lot of lights!

John went on to describe some of the earliest lighthouses stating with the first one, which was on Pharos in Alexandria and was built circa 200BC. It was badly damaged by 3 earthquakes between 900AD and 1300AD and eventually became a ruin. It was operated at night by fires on top of it and by day by mirrors that reflected the sun.

The earliest lighthouse in Britain was at Dover and was built by the Romans. It was clear from reports that not everyone wanted to have lighthouses around their shores. The use of lights to guide shipping could, of course, also be used by smugglers who used them to wreck ships and steal their goods. An account in 1736 described one such case where a ship was driven onto Perrin Sands to steal the cargo.

In the early days it was not just lights that were used to guide ships. Other markers such as hills, mills and churches; the white painted church tower at East Brent being one example.

He explained the difference between onshore and offshore lights with offshore lights being either on small islands such as Lundy or towers built on rocks.

Using photographs, drawings and old documents John then described lighthouses in the Bristol Channel. The St Nicholas Chapel in Ilfracombe, he explained, is the oldest example of a tower and has been in use as such since the Middle Ages. In those days the light came from fires.

Hook lighthouse was also lit by fire and is situated at Wexford. It was built by monks in the C14th and is still in use today.

As John explained, the increased trade into the Bristol Channel had made it inevitable that more lighthouses would be built.

The first lighthouse at St Ann’s Head was built in 1662 and was coal–fired. Charges to shipping for entering ports at this time could only be made when the ships were in port and a patent had to have been granted to allow charges to be made. At St Ann’s in 1662 the charges were only voluntary and not surprisingly they found that very few people paid them money and so they pulled down the lighthouse. Recognising the need for a lighthouse due to the number of ships being wrecked, however, Trinity House granted a patent for a lighthouse on the site and two towers were built in 1714, which were also coal-fired. The charge was 1d per ton of cargo for British vessels and 2d per ton of cargo for foreign ships. The current lighthouse was built in 1844.

Flatholm: Local people had to agree to the building of a lighthouse and also had to run them and apply for a Government patent. Merchants and trading gentlemen living in Bristol wanted to build one at Flat Holm but couldn’t get the necessary agreements until a ship carrying 60 soldiers was lost in 1735.

On December 3rd 1737 they received a patent and a lighthouse was built on the island. The island also had an isolation hospital. The light was produced from coal which came from Swansea but by 1753 the two men who had started it went bankrupt and Caleb Dickinson who had lent them the money to build it ended up owning it. John explained that the Somerset Record Office has a large number of documents relating to the family, which show the accounts relating to the lighthouse.

John went on to talk about the people who ran the lighthouses. The onshore ones had people living nearby but offshore ones were different. Here, there were normally 4 keepers per lighthouse. This was because in the early days there were only 2 keepers but on one occasion one of them died and the other was so worried that he might be accused of murder that he took the body and hung it outside the lighthouse in a bag to prove that the man had died of natural causes.

After that they always had 4 keepers per lighthouse, 3 on duty and one on leave. These would be a principal keeper, an assistant and a supernumerary or trainee, all of whom worked 8 hour shifts. Their duties were clear and included keeping a log, reporting on wind speed, visibility, barometric pressure and windforce which apparently they guessed by how it felt on their cheek Since cleaning was also part of their duties they didn’t touch the brass rails on the stairs. Apparently no keeper would touch the rails!

Reading from her account of her life on Flat Holm, John told us about Mrs Trezise who was there in 1926-9. At that time Flat Holm was considered the worst land lighthouse to work in but when her husband was appointed keeper there she was delighted. There were 9 people there at that time including the caretaker and his wife who looked after the hospital. In one year the weather was so bad that they couldn’t get provisions for nearly two months and had Christmas with no perishable food. To make matters worse one woman had a baby during this time and they nearly ran out of Nestlés milk!! In 1929 it was re-designated as a Rock Lighthouse and Mrs Trezise went to live in Swansea.

Mrs Trezise’s account can be read here

Instructions from those days included: lighting lamps and trimming them every three hours, maintaining watch, no bed or sofa was to be kept in the lantern room or watch room, everything had to be cleaned and polished and they should not cause any damage. They also had to either attend Church or the Principal Keeper had to conduct a service and deliver the sermon. Temperance, cleanliness and high standards of morality were also key demands.

John also talked about how the various lights were used and how they operated. The Mumbles lighthouse in 1794, for example, had two levels of fires. Lighting was by candles and bonfires until the introduction of lamps and clearly there were many dangers. After this they had oil lamps. Improvements came with the Argand lamp, which had an air flow up the centre which was more efficient than previous versions and was lit with heavy oil like whale oil. Later versions used kerosene. Improvements continued and soon came the introduction of reflectors at the back and large lenses at the front. Later still they used the Fresnel lamp which had rotating optics and was much more efficient.

John went on to talk about Burnham lighthouses. In 1895 a newspaper gave the origins of the Burnham Lighthouse and stated that legend had it that originally the “lighthouse” was simply a candle in the window of a cottage which a woman had put there to guide her husband home and due to its success was asked to do it permanently. Although this story has often been repeated, John said it was not quite accurate. Newspapers in 1846 reported that the first light was actually lit by a person on Stert Island, then an isthmus, to warn sailors of the dangers. Whatever the truth of the matter the first actual lighthouse was erected by the Rev David Davies of St Andrew’s Church, who paid for a tower to be built next to the church in 1801. The number of vessels using the port increased after the lighthouse was built from 600 to 3000 and Trinity House took over its control from Rev Davies. A second tall lighthouse was put at the end of the channel and a third was erected on the beach because there was a blind spot. John explained that the one on the beach still works and that now all lights are remotely controlled.

In conclusion John mentioned briefly Watchet harbor light, Blackmore Point at Portishead which had a post in the middle to help rotation of the light and which was turned by a clockwork mechanism powered by a weight which had to be wound up every 2 hours, and finally Lundy which had a lighthouse situated so high that the top was often lost in the mist, so much so that another lighthouse had to be built lower down.

At which point time ran out. It was a fascinating story and clearly much more to be told.

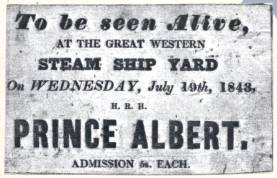

it; this was the Great Western Steamship Company and the directors decided to appoint Isambard Kingdom Brunel as their chief consulting engineer. Although Brunel had never designed a ship before, he was asked to do so on the basis of his work with the Great Western railway.

it; this was the Great Western Steamship Company and the directors decided to appoint Isambard Kingdom Brunel as their chief consulting engineer. Although Brunel had never designed a ship before, he was asked to do so on the basis of his work with the Great Western railway.

Although the contract for the Royal Mail to the US was subsequently given to Cunard the company realised that iron ships were the way forward.

Although the contract for the Royal Mail to the US was subsequently given to Cunard the company realised that iron ships were the way forward.

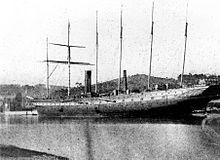

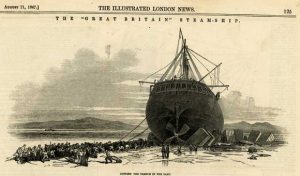

Brunel travelled over there to oversee the ship’s recovery. Fearing the approach of winter storms he made a breakwater around the stern of the ship which saved it from the worst of the winter weather but, although it was successfully re-floated and returned to Liverpool the following year, the cost involved had been enormous and the Great Western Steamship Company went bankrupt, forcing the sale of the SS Great Western and the SS Great Britain to Gibbs Wright and Co in 1847

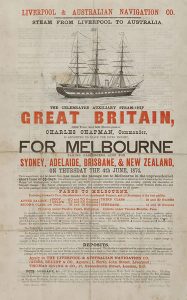

Brunel travelled over there to oversee the ship’s recovery. Fearing the approach of winter storms he made a breakwater around the stern of the ship which saved it from the worst of the winter weather but, although it was successfully re-floated and returned to Liverpool the following year, the cost involved had been enormous and the Great Western Steamship Company went bankrupt, forcing the sale of the SS Great Western and the SS Great Britain to Gibbs Wright and Co in 1847 When gold was discovered in Australia in 1851, there was a sudden massive demand for ships to take people out there and the ship underwent a radical re-fit by the new owners Gibbs Bright & Co to become a 3 masted square–rigged sailing ship with auxiliary engines, which could do the voyage non-stop from Liverpool to Melbourne. In 1852 they carried 700 passengers. It cost 70 guineas (equivalent now to £5000) to travel to Melbourne first class and even in steerage it cost the equivalent of £1500 in today’s money. The journey took just 2 months.

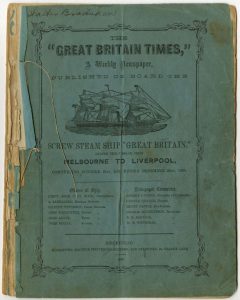

When gold was discovered in Australia in 1851, there was a sudden massive demand for ships to take people out there and the ship underwent a radical re-fit by the new owners Gibbs Bright & Co to become a 3 masted square–rigged sailing ship with auxiliary engines, which could do the voyage non-stop from Liverpool to Melbourne. In 1852 they carried 700 passengers. It cost 70 guineas (equivalent now to £5000) to travel to Melbourne first class and even in steerage it cost the equivalent of £1500 in today’s money. The journey took just 2 months. invaluable resource in piecing together what life was like on board.

invaluable resource in piecing together what life was like on board.

The cost of repairing the ship was considered uneconomical and so she was sold to the Falkland Island Company for £2000 where it became a warehouse primarily for coal, wool and grain and was moored at Port Stanley Harbour. It remained there until it was so rotten that they moved it to Sparrow Cove in 1937 where it was scuttled. Despite being abandoned, she still had some uses. In WWI she was used as a bunkering station and in WWII plates were taken off her to repair damage which had occurred to the HMS Exeter during the Battle of the River Plate. Throughout her time at Sparrow Cove the children of the island greatly enjoyed her presence, using her as an adventure playground and picking mussels from the hull to take home for their tea.

The cost of repairing the ship was considered uneconomical and so she was sold to the Falkland Island Company for £2000 where it became a warehouse primarily for coal, wool and grain and was moored at Port Stanley Harbour. It remained there until it was so rotten that they moved it to Sparrow Cove in 1937 where it was scuttled. Despite being abandoned, she still had some uses. In WWI she was used as a bunkering station and in WWII plates were taken off her to repair damage which had occurred to the HMS Exeter during the Battle of the River Plate. Throughout her time at Sparrow Cove the children of the island greatly enjoyed her presence, using her as an adventure playground and picking mussels from the hull to take home for their tea.

ven a guided tour of the cave where bones can still be seen. These Pleistocene animal bones were discovered in the early part of the 19th century on land owned by George Henry Law, the Bishop of Bath and Wells and, although many of them were removed, some are still carefully stacked around the walls of the chamber.

ven a guided tour of the cave where bones can still be seen. These Pleistocene animal bones were discovered in the early part of the 19th century on land owned by George Henry Law, the Bishop of Bath and Wells and, although many of them were removed, some are still carefully stacked around the walls of the chamber.

urday May 20th with a visit to Christon Church. Christon is a small village on the southern slope of Mendip and at the foot of Flagstaff Hill. It looks across the Lox-Yeo valley to Crook Peak and as people gathered many commented on the stunning setting and how tranquil and peaceful the valley must have been before the coming of the motorway.

urday May 20th with a visit to Christon Church. Christon is a small village on the southern slope of Mendip and at the foot of Flagstaff Hill. It looks across the Lox-Yeo valley to Crook Peak and as people gathered many commented on the stunning setting and how tranquil and peaceful the valley must have been before the coming of the motorway. The chancel has been divided into two by a reredos to create a small vestry under the east

The chancel has been divided into two by a reredos to create a small vestry under the east