The Great Eastern

We had an excellent talk by Philip Unwin, a volunteer with the SS Great Britain Trust, on The Great Eastern, Brunel’s 3rd and last ship. As Philip explained, she was huge being twice the length, width and draught of the SS Great Britain. Her size, however, caused several problems wherever she went and that together with various financial problems and a degree of bad luck led many to think she was jinxed.

She was designed by Brunel to take 4000 passengers to the Far East without refuelling and for this reason had both propellers and paddles as many of the places it was intended to go to had shallow waters. 5 engines were required to provide enough power to drive the ship.

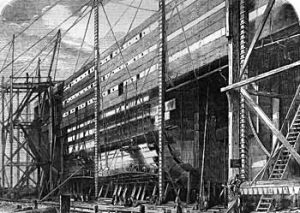

Brunel discussed his design with John Scott Russell, an excellent engineer and shipyard owner in Millwall, who he had met at the Great Exhibition in 1851 and found that Russell had had a similar idea. He approached the Eastern Steam Navigation Company who agreed to fund the project. Brunel estimated that the cost of building the ship would £500K but Russell put in a  much lower bid which Brunel accepted and, in 1854, they began building the ship on a timber grid, the remains of which can still be seen. Philip showed us several plans of the design of the ship.

much lower bid which Brunel accepted and, in 1854, they began building the ship on a timber grid, the remains of which can still be seen. Philip showed us several plans of the design of the ship.

Brunel was, apparently, a difficult man to work with and insisted that he had to authorise every change needed to be made during the ship’s construction but of course this was impossible as he had a lot of other projects to supervise. This was to prove significant.

The ship had a double iron hull which required 3 million rivets that had to be driven by hand, enormous 50ft paddles, and a cast iron screw propeller which was 24 ft in diameter. When complete in 1854 it was said to be the largest man-made moveable object.

The cost of constructing the ship was enormous and this, together with the amount of time it took meant that the ship had 2 different owners all of whom had lost money before the launch.

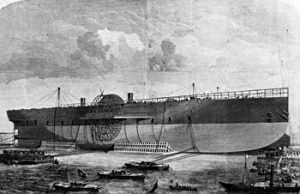

Launch Day was set for 3 November 1857 . Because of its size it had been designed to be launched sideways using hydraulic rams. The first ones they used were inadequate for the job and Richard Tangye from Birmingham was asked to provide stronger ones. This he did bringing them down from Birmingham – an enormous task in itself but it was very good publicity for him.

. Because of its size it had been designed to be launched sideways using hydraulic rams. The first ones they used were inadequate for the job and Richard Tangye from Birmingham was asked to provide stronger ones. This he did bringing them down from Birmingham – an enormous task in itself but it was very good publicity for him.

Brunel had hoped to launch the ship with a minimum amount of publicity but, as Philip explained many people had been watching the building of the ship and it had been a real tourist attraction. Even Queen Victoria apparently made a visit although she was most displeased at the stench coming from the Thames. The directors, who were in need of any money they could get, decided to capitalise on the publicity and sold 3,000 tickets for the event at 5 shillings each. Brunel was not pleased.

The ship was launched by attaching chains from the ship to two barges which were securely moored so that when the rams pushed the ship down the slip the barges would hold it, but on the first occasion the anchors of the barge dragged and the ship only moved 6 feet. The next time it was tried there was no movement at all as the chains broke and various people were hurt. In the end it took 3 months before she was floated out and moored. The time taken and the ship’s sheer size led to a lot of mockery and there was a Punch cartoon showing Brunel on board with a hot air balloon, a cattle show and other things which ridiculed the whole process. Ironically this presaged how she would end up.

The ship was launched by attaching chains from the ship to two barges which were securely moored so that when the rams pushed the ship down the slip the barges would hold it, but on the first occasion the anchors of the barge dragged and the ship only moved 6 feet. The next time it was tried there was no movement at all as the chains broke and various people were hurt. In the end it took 3 months before she was floated out and moored. The time taken and the ship’s sheer size led to a lot of mockery and there was a Punch cartoon showing Brunel on board with a hot air balloon, a cattle show and other things which ridiculed the whole process. Ironically this presaged how she would end up.

Brunel himself was annoyed that the launch had not been done the way he had planned and had been humiliated by the launch. He died 10 days later, in 1858, following a stroke. Although it was said that the ship had killed him he had, in fact, been quite ill for some time and suffered from Bright’s disease and by the time the ship was built he was also exhausted. The 48 cigars a day he apparently smoked probably didn’t help either.

The total cost of the launch was £170K. The ship with an estimate of £500K to build had eventually cost £730K and still needed to be fitted out. Her owner, the Eastern Steam Navigation Company was now in severe financial difficult and a new company, the Great Ship Company, was set up which bought out the original shareholders. They bought the Great Eastern for £160,000 and had enough capital to pay for the fitting out. Philip said this was a bargain since there was at least that value of iron there although there was less than Scott Russell said he had provided!

Philip showed pictures of the inside of the ship which was extremely luxuriously fitted out.

Philip showed pictures of the inside of the ship which was extremely luxuriously fitted out.

It was a very grand ship and was completed in 1859. Despite the fact that Brunel had intended that the ship sail to the Far East and advised that it should never cross the Atlantic, the first voyage in 1860 was to America with 400 passengers only 35 of whom were paying and so there was no profit. She sailed with a new captain as the original one had drowned in an accident in Southampton.

This was, according to Philip, the first intimation that the ship was jinxed.

In 1861 it made its second trip across the Atlantic, having been chartered to carry 2400 troops to reinforce the British garrison in Quebec in response to American threats to move into Canada. Although this trip did make a profit it also turned into a PR disaster. The civil war was going on in America and not many people were interested in the ship. In order to promote it, therefore, the Captain decided to offer paying passengers a cruise. 1500 people signed up, far more than they had crew for and so they hired local labour. The cruise proved to be a total disaster; the local crew members were often drunk and rude to the passengers, there was not enough food and fresh water and there were a lot of complaints. Fed up with the state of affairs, Philip explained that many people grabbed bottles of booze and got drunk, going onto the upper deck to sleep. Unfortunately for them there were 5 funnels all belching out black smoke and when they awoke in the morning they were black. With not enough fresh water to wash themselves, this added to the complaints. When they got back to New York the ship owners were used by the local press for gross inefficiency and misleading advertising.

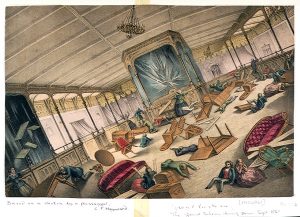

The third voyage also had problems. During a very bad storm the rudder broke although it was 24 hours before the passengers realised what had happened. The problem was that when the rudder flapped about it damaged one of the paddles necessitating the other paddle to be stopped plus the engines. Philip read an extract from an account written by one of the passengers in which he described how nothing was chained down, tables and chairs tumbled, mirrors were smashed and broken, the grand piano broke away and in the dining room and galley there was flying crockery, food and cutlery. It was mayhem and must have been terrifying for the passengers and crew.

One of the passengers, who was an engineer, had a plan to resolve the issue but the Captain refused to listen to him. The passengers took matters into their own hands and the passenger committee demanded that the Captain try out the plan. This involved putting chains around the rudder head to control it. In order to do this it was necessary for someone to go over the side to secure a chain to the rudder. One brave sailor volunteered and managed to do it. Once they got underway again, the passengers had a whip round and were able to give him £100. A sizeable amount in those days. By the time the ship was repaired, however, the ship was off course. A small coaster from America came alongside and offered to accompany the ship overnight. Although this must have been a reassurance to the passengers in reality, as Philip explained, they couldn’t really have done very much. What they did do, however, was to charge the ship owners demurrage because of the delay they incurred getting to port. It was yet more expense for the owners.

After the necessary repairs the ship made 3 more voyages but on the last to New York she got a gash in the hull. This became known as the Great Eastern Rock incident. Although they arrived safely in New York the ship was listing badly and when they examined the ship they found that a section between the hulls was full of water. Although the gash was very large and bigger than the one that sunk the Titanic, the ship had survived because of the double skin. Due to her size it was impossible to repair her in a dry dock and so a cofferdam was built to effect the repairs.

There were three more voyages but the company was running out of money and in January 1864 the ship was put up for sale and was bought by a new company, The Greater Eastern Steamship Company with the purpose of laying a transatlantic cable.

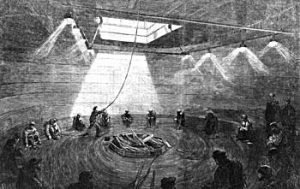

In April 1864 the ship was chartered to the Telegraph Construction Company. The Great Eastern was the only ship big enough to tak e the length of cable required for this huge operation, and it took five months just to load it.The cable was 2000 miles long and 1 inch in diameter. All this had to be accommodated in the hold and paid out gradually to a depth of about 2 miles. The first attempt took place on 14 July 1865 andthe cable broke 5 times. Each time the cable had to be brought back into the ship to be repaired. They had to find cable, then draw it up and as it had to be brought in over the bow they had to turn the ship round each time. It was very tedious and each time took 12 – 17 hours. As Philip said, it must have been a soul destroying job.

e the length of cable required for this huge operation, and it took five months just to load it.The cable was 2000 miles long and 1 inch in diameter. All this had to be accommodated in the hold and paid out gradually to a depth of about 2 miles. The first attempt took place on 14 July 1865 andthe cable broke 5 times. Each time the cable had to be brought back into the ship to be repaired. They had to find cable, then draw it up and as it had to be brought in over the bow they had to turn the ship round each time. It was very tedious and each time took 12 – 17 hours. As Philip said, it must have been a soul destroying job.

The second attempt using a lighter and stronger cable was successful and the transatlantic cable linking Ireland to Newfoundland was completed on 1 September 1866.Messages were being sent back all the time reporting their progress and there was much excitement.

It was then chartered to a French company who laid a cable from Brest to New York and also one from Aden to Bombay. It was then chartered to a French company who wanted to use her as a cruise liner and they put back all the furnishings. This was never very successful and she was eventually laid up in Milford Haven.

At the end of her life the ship became much like the one lampooned in Punch. She was, amongst other things, used as a fairground and went up and down the Mersey advertising Lewis’s Department Store. In 1888

At the end of her life the ship became much like the one lampooned in Punch. She was, amongst other things, used as a fairground and went up and down the Mersey advertising Lewis’s Department Store. In 1888

she was sold for scrap and was broken up on the banks of the Mersey. She was so strong that it took 2 years to break her up.

A sad end.