A lively and informative talk about Friendly Societies was given at the November meeting by Philip Hoyland. Philip explained that Friendly Societies were established at the end of the eighteenth century to enable the working man to cover the costs of medical care, any periods of unemployment nd to pay for funeral costs. In 1793 the Friendly Society Act was passed requiring Friendly Societies to be licensed and John Tidd Pratt became the Registrar based in London. Records show that by 1801 five thousand societies had registered and that four years later in 1805 the number had increased to ten thousand. By the beginning of the twentieth century six million people were using the system and funds had increased to £14 million. The friendly societies were the precursor of the National Insurance System and, at a time of increasing unemployment, had become very important.

So, how did the system work? Working men were eligible to join a Friendly Society between the ages of 16 and 35 but they could then remain members for life. They had to pay a subscription to belong and this varied from 8d to 1/- a week paid monthly. Fines were imposed on anyone who got behind with these payments. Members also had to pay for their own rule book and brass pole head and provide 4 gallons of cider at the first meeting they attended. The money collected was kept in a strong box by the treasurer and disbursed at times of need. Medical expenses would be covered where necessary and if a man was too ill to work he would receive sufficient funds to survive. At a time when the average weekly wage was 11/-, the average pay out would have been of the order of 6/-. A steward was appointed from among the club members and was required to make a weekly visit to anyone claiming sickness benefit. This ensured that there were no malingers but it was not a popular task and many preferred to pay a fine rather than perform it. On a man’s death, his widow would receive £2 to £3 to cover the cost of his funeral and members would also have a whip round for her. If a wife died a man would receive £5! Clearly his loss was considered much greater than hers. Friendly Societies would also lend money at no or low rates of interest and if calls on the funds had not been great for a period of time and money had accumulated there might be a share out rather like a dividend. Societies therefore performed some of the functions of a bank.

Societies, or clubs as they were often called, would meet once a month in a club room. This was often in a pub and everyone there would be entitled to 2d worth of beer. This must have led to quite a convivial atmosphere and possibly accounts for the poor reputation that club nights developed among the upper echelons of society. In spite of this reputation, members had to adhere to the rule book and standards were high. Rules varied between societies but misdemeanours such wearing a hat, playing certain games such as marbles or quoits, bringing a dog into the room, rioting or wrestling and even adultery could all incur fines which were then added to society funds.

Once a year there was a very important Feast Day, Club Day or Walking Day as it was sometimes called, the costs of which were paid for out of funds. The men would gather in their club room dressed in their best clothes (no smocks were allowed) and wearing a sash and a flower or tutty in their button-hole. They would then march to church beneath their club banner each man holding his club brass aloft on a long pole and they would be accompanied by a brass band. The church service would be followed by a procession round the area visiting all the big houses where further donations would be made to club funds. Following that, the serious business of the day began with a massive feast and much drinking. There was also a variety of entertainments to follow the feast. These might include dancing, games or even a fair.

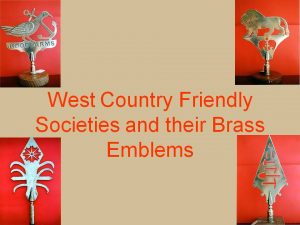

Philip had brought a wonderful collection of gleaming club brasses with him and the story of the brasses is an interesting one as the tradition of carrying brasses is not countrywide. They only seem to occur in Somerset and its surrounding counties and the origin of them is not clear unless they relate in some way to the ea

rlier guilds. Local brasses were made in the Bristol or Bridgwater foundries and the cost to each man would have been of the order of 1/6. This would have been quite a considerable sum of money atthattime. The design of the brasses was often related to the location of the club room. If the location was in a pub then the pub name would be depicted. In Combwich the club room was at the Anchor Pub so the brass was in the shape of an anchor; at Kilve they met at the Hood Arms so the brass was a chuff and anchor – the Hood family crest etc. etc.

There were also female friendly societies, some of which in this area were established by Hannah More. How they were funded is not clear as subscriptions were only ½ d a week but Hannah More may well have contributed financially to them. On marriage a woman would receive 5/-, a pair of stockings and a bible. At the time of ‘lying in’ the benefit was 7/6.

The Friendly Societies continued in this form until 1948 when Aneurin Bevin who, for many years had been involved in his local variant of a Friendly Society the Tredegar ‘Sick Club’, introduced the National Health Service, or as he put it, “Tredegarised the nation”! Since then Friendly Societies have become less important but many still exist and still process to church once a year. Their function today is as fund raisers for charity.

Philip completed his talk by explaining how he kept his stunning collection of brasses in immaculate condition. It seems that a combination of Betterware paste and a product called Renaissance will preserve the surface without abrasion and the inevitable loss of surface decoration or the use of elbow grease.